Fifty years ago on August 29, 1970, a group of teenage boys who grew up on the same, working-class street in East Los Angeles did something out of character. We joined a protest march.

On most hot, smoggy weekends in late summer we’d hang out under the Chinese elm in front of Jerry and Danny Viramontes’s house on Ferris Avenue. We’d argue sports and music to no end. Who was the better rock guitarist, Carlos Santana or Eric Clapton? Mostly though, we’d call around for that night’s parties. We lived for garage rock’n roll. Poor East L.A, so far behind the opportunity curve, so blessed with garages.

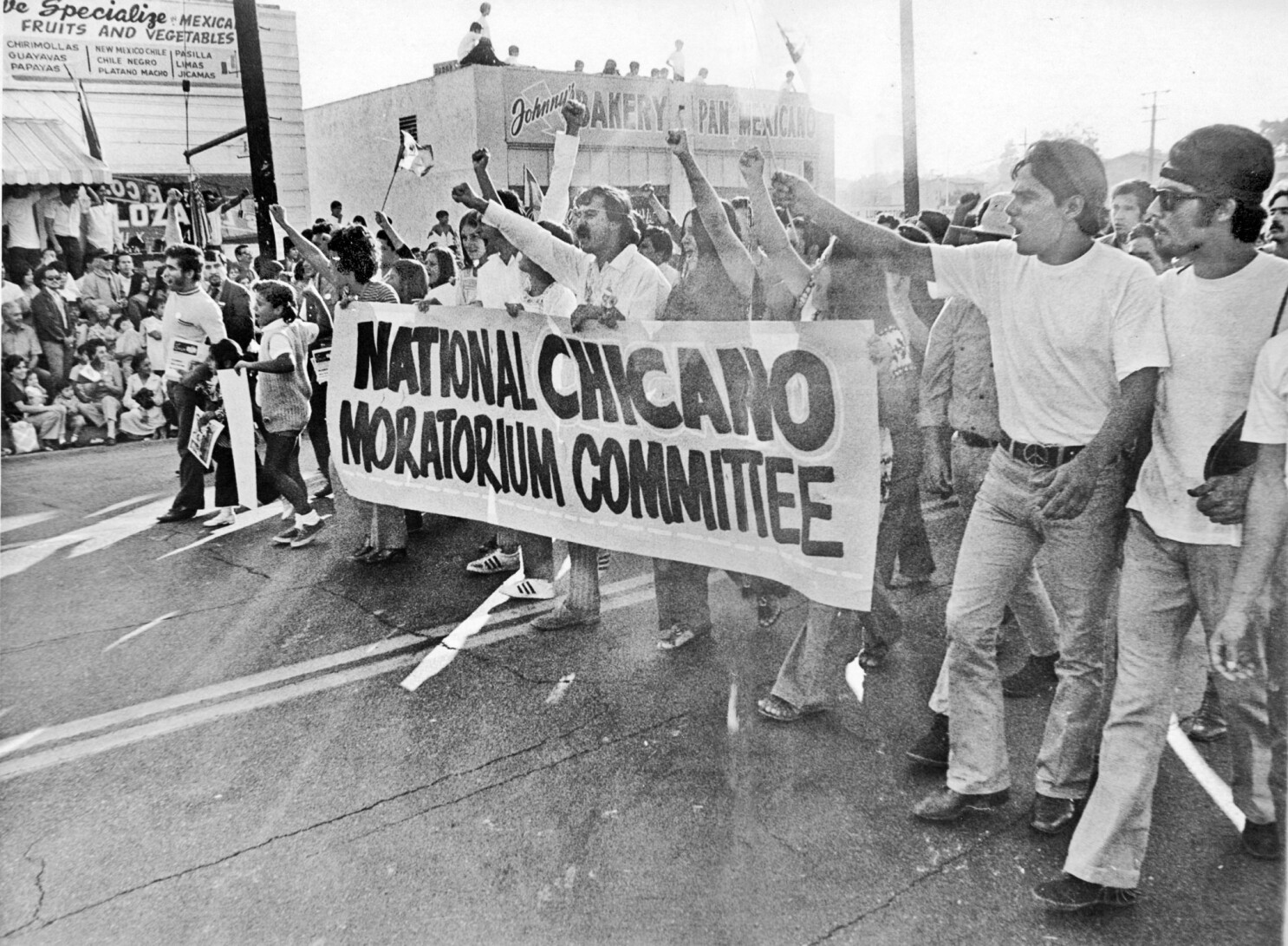

But on that Saturday in August, we decided to join some 20,000 demonstrators for one of several National Chicano Moratorium marches across America to stop the Vietnam War and end its heavy toll on Brown families. (If Blacks can get a capital “B,” why can’t we?)

I remember my surprise at seeing so many couples pushing baby strollers, brothers and sisters of guys in 'Nam, their parents and even some grandparents. Every marcher seemed to have somebody over there. My buddies and I, we worried about Robert Delgado and Julian Felix. Theirs was a familiar story in East L.A.

During Easter break before graduation from Garfield High School, they and four other classmates joined the Marines on the same day rather than wait and get drafted.

“The word 'draft' kept pecking at my head like a woodpecker,” Robert told me this week. “I still love my country, but I was no flag waver. Basically, we signed up out of necessity. We had nowhere else to go.”

Two years before the Moratorium, the Tet Offensive in 1968 had convinced enough Americans that the war was not winnable or worth the cost. Yet the body counts continued.

I graduated a year after Robert from Garfield. Unlike him, I opposed the war, but I was no flag burner. If drafted I would go, because I couldn’t bring shame upon my family and community. I could read and type. That might save me from combat, I hoped, but who was I kidding? I knew I’d still be part of the war machine. By the time the Moratorium came around, I was praying we could actually suspend the war.

Soon after the march started, it turned into something of a high school reunion, neighborhood celebration and grass-roots rally without politicians. It was down-home, fun, optimistic and confident, a treat for people-watchers like me.

Soon after the march started, it turned into something of a high school reunion, neighborhood celebration and grass-roots rally without politicians. It was down-home, fun, optimistic and confident, a treat for people-watchers like me.

I especially remember the skinny guy with a goatee and bullhorn. Like a Fiddler on the Roof, he kept popping up on buildings when least expected. He’d lift the bullhorn with his thin arms and chant “Chicano power” and “Sí se puede!” We in the street chorus chanted back with glee. I still wonder whatever became of him.

Our feet sizzled as we ended the march at Laguna Park. The crowd settled in for a program of anti-war speeches, music and Mexican folklorico dancing. Of course, we noticed the usual company, Los Angeles police officers and county sheriff’s deputies in riot gear. I wanted to stick around but my buddies weren’t interested in listening to college-boy speakers. So we jumped into a friend’s Chevy Nomad and went home.

Soon enough from my porch, I saw smoke rising over the park and police helicopters buzzing about. I ran down the street to see what was happening for myself. I didn’t last long out there. One whiff of tear gas and the sight of charging cops sent me running into a kind stranger’s house filled with frightened marchers.

After 50 years, we can rely on only a handful of trustworthy but rather tardy investigations and journalistic reports: A liquor store owner reported a theft and minor disturbance. An officer, never identified, ordered the police to disperse the crowd. They did, with tear gas projectiles and billy clubs. By day’s end, dozens were injured and a few died.

Among the dead was Ruben Salazar, the first role model I had as an aspiring writer. The popular Los Angeles Times columnist and Spanish-language TV news director was killed by an ill-trained deputy who had fired a wall-busting tear gas missile into an open bar. Ruben had gone in to rest a bit from reporting the event. He was sitting at the counter when he took the direct hit.

Ruben had started writing forcefully about police abuse and told some journalist friends that he feared for his life. One investigation concluded his death was an accident of police ineptitude. East L.A. is still waiting for a better answer.

I remember Ruben in other, more personal ways. My father and I were avid newspaper readers. A truck driver, “Pops” brought home the afternoon Herald-Examiner, the city’s working-class paper. My grandmother sent me to the corner market for the Spanish-language La Opinion. With a wink, she’d give me enough to also buy a copy of the Los Angeles Times.

I remember Ruben in other, more personal ways. My father and I were avid newspaper readers. A truck driver, “Pops” brought home the afternoon Herald-Examiner, the city’s working-class paper. My grandmother sent me to the corner market for the Spanish-language La Opinion. With a wink, she’d give me enough to also buy a copy of the Los Angeles Times.

Pops hated the Times. He never forgave it for siding with sailors who attacked Mexican-American “zoot suiters” during World War II. By the late 1960s, the Times realized it didn’t know much about the city’s large Mexican-American community and their rebellious Chicano youngsters.

Salazar was in Mexico City for The Times when he got the call to come home and cover Mexican-Americans. After a clunky start, Ruben began to offer unique insights into the character of a complex culture.

For example, he asked, what’s a Chicano, anyway?

In one short sentence in one column, the columnist summed one of the most understated goals of their movement: “A Chicano is a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself.”

Salazar was onto something bigger, I think, than he knew at the time. The adoption of a Chicano identity was a thundering declaration of cultural freedom. No longer would a white American culture descended from Western Europe dictate the nature of American identity or patriotism.

The Civil Rights Movement had delivered equality and outlawed racial discrimination, at least on paper to start. Now it was time for equality of heritage, history, language, social values, food, music – the many ways, great and small, in which we live and that make up a people's distinct culture and group identity.

That Salazar column clicked with Pops. He had the dark skin and facial features of our northwest Mexican Indian ancestors, and he had felt the sting of racism here and in Mexico. Salazar offered us a common theme: The Mexican-American father and his Chicano son were as non-Spaniard in Mexico as they were non-Anglo in the United States, and thus free to join a new, bona fide American culture with pride and equal standing.

In another column, Ruben demonstrated how journalists can write about minority groups intimately and apart from politics. He went to Bella Vista, the most desirable neighborhood within East L.A, and explained why it was the Mexican-American Shangri-La.

My older sister and I had long bugged Pops and Mom to move us to Bella Vista. It makes me cringe now, but we had become ashamed of our modest, tiny house and anxious to rid ourselves of barrio, underclass stigma. Pops refused, explaining patiently that Mom would have to return to work and leave us alone at home. Well, when a good man’s children don’t appreciate the best home he can offer, that could drive him to drink.

And he did, oftentimes at the Silver Dollar Café, the same bar in which Salazar met his fate. Pops had become a fan of his column, and never stepped into the Silver Dollar again.

Later that year, Robert Delgado returned home horribly wounded, riddled by shrapnel and half-blinded by a grenade blast. My parents joined the solemn procession of neighbors to the Delgado house, but they would not let me and my little brother see Robert until much later.

“I remember one weekend 15 people visiting me on a Saturday and 15 more people on Sunday,” Delgado told me. "Those are the things you never forget.”

The Moratorium probably marked the peak of the Chicano Movement. But doesn’t matter if it burned out, lost relevance or wiped out under a massive wave of immigration from Mexico and Central America.

Yesteryear’s Mexican-Americans became yesterday’s Chicanos, who became today’s Hispanics or Latinos, who just might become tomorrow’s Latinx. It’s all wonderfully free. Let assimilation happen between and within cultures, I say, just don’t let any one group call the shots ever again.

As for me, I hope I followed in Salazar’s footsteps. When I was a young crime reporter in Riverside, Calif., the city’s police chief actually banned me from headquarters for my reports on his department’s taste for excessive force. The ban lasted only one day, but it remains one of my sweetest prizes in journalism.

As fate would have it, today’s coronavirus pandemic has put the brakes on a 50th Anniversary Moratorium memorial march. But I just might walk the route, anyway, quietly, and with a face mask. I will stop at the former Silver Dollar Café to honor Ruben Salazar. And if I can muster enough imagination, I just might spot the elusive Chicano Fiddler on the Roof again.